1.「移動する人生」において宙吊りにされる主体性

1. Subjectivity suspended in a “life on the move”

僕は幼少の頃から父親の転勤で移動が多く、いわゆる郊外の国道沿いのマンションのようなところで暮らしてきた。そのためか、どこに行ってもよそ者や根無し草のような感覚が拭えない。大人になってからも、特段意識的に移動しようと思ってきたわけではないのだが、特定の地に留まる理由も特になかったので、人生このかた移動に移動を重ねてきた。

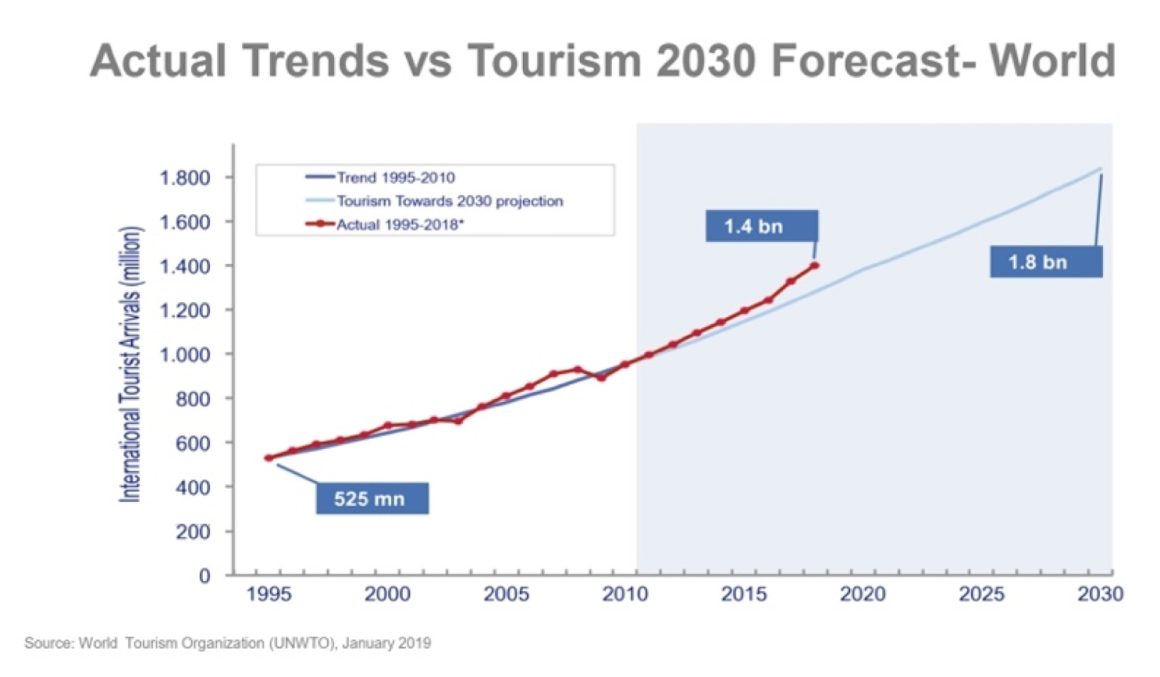

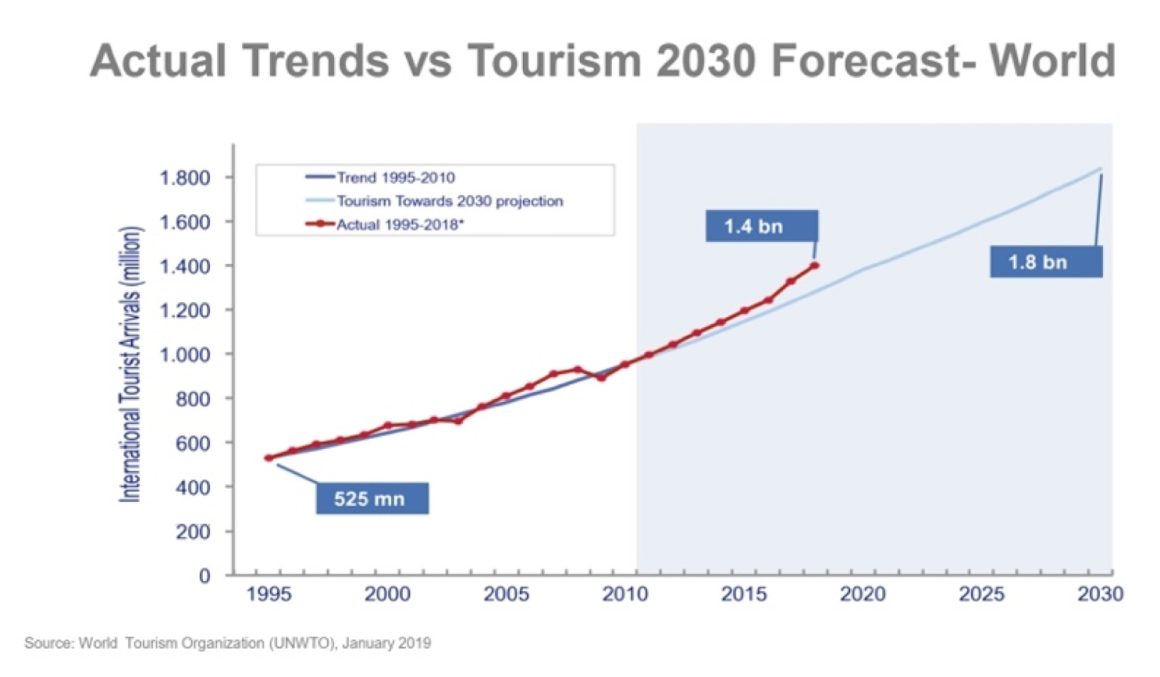

ある土地に根差して暮らすのではなく、「移動し続けることが人生そのもの」になるような生き方は、人間のアイデンティティを揺らがせる。だがそれは、現在では実は、現代社会を生きる多くの人々が本質的に抱えている生き方ではないだろうか。付け加えると、僕は決してアウトドアを好むわけではなく、どちらかというと家で小説や哲学書をつらつらと読んでいる方を好むが、にもかかわらず、映像撮影の仕事やアーティスト・イン・レジデンスの滞在制作でヨーロッパ・東南アジア・アフリカ各地を17ヶ国ほど転々と移動し続けてきた。この数字が多いのか少ないのかは分からないが、世界各国で都市化が進んで移動が容易になり、国連世界観光機関(UNWTO)の世界観光統計(図1-1)[1]を見ても、予想を覆す速さで観光客の数が右肩上がりに増え続けている今日において、僕の「移動する人生」が現代社会の一端を象徴していることは間違いないだろう[2]。

図1-1 UNWTO世界観光統計

僕が最初にカメラを手にしたのは18歳頃だっただろうか。それは中古のフジカZ800という8mmフィルムのカメラであった。1つのカセットで3分間の撮影ができるが、色温度や露出を正確に考えて照明を当てないと普通に風景を撮影することもままならない代物であった。当時から20年以上が経つが、カメラはなにがしかのHi8規格の機体からソニーのVX2000へと変化し、そのあとはコンデジやiPhoneで遊びつつ、最近ではパナソニックのGHシリーズを愛用しながら、様々な映像を記録してきた。

映画や実験映像を好み、自ら映像を撮りたいという動機も当然あったのだが、それ以上にカメラを抱えて出来事に関わることに興味があったのではないだろうか、といま自分自身の過去を振り返りながら感じている。そのような意味では、昨今の持ち運びが便利で高機能である小さなカメラは、様々な出来事に介入していくために、昔と比べて非常に使い勝手が良い。加えて、暮らしの中に映像が溢れているので、カメラを抱えて出来事に介入することの特殊さが薄れており、カメラを抱えたままでも対象との関係が築きやすいこともまた好ましく思われる。

振り返ってみると、僕の根無し草の感覚は、出来事の当事者感も同時に喪失させており、どうも出来事に積極的に関わることのできない、主体性を欠いたどこか斜に構える性質が身に染みていた。そのような僕がカメラを持って出来事に関わると、当事者でなくともその場にいる必然性を感じられて、それが僕には心地よかった。対象との距離感や自分がその場にいても違和感がない感覚は、出来事の当事者と僕とのあいだで独特な関係性を築くように思われた。そしてそれは、カメラを介してこそ感じられる感覚だった。このときの感覚、つまり当事者=ウチでもない、無関係=ソトでもない、その「あいだ」における宙ぶらりんの視点から生まれる関係性が、事後的に気づいたことだが、昨今の僕の活動の根幹にある。

ウチでもないソトでもない、その「あいだ」における宙ぶらりんの視点、この感覚を象徴するテキストを村上春樹(1949-)が『国境の南、太陽の西』の中で綴っている。既に25年以上前の小説である。

僕はこれまでの人生で、いつもなんとか別な人間になろうとしていたような気がする。僕はいつもどこか新しい場所に行って、新しい生活を手に入れて、そこで新しい人格を身に付けようとしていたように思う。僕は今までに何度もそれを繰り返してきた。それはある意味では成長だったし、ある意味ではペルソナの交換のようなものだった。でもいずれにせよ、僕は違う自分になることによって、それまでの自分が抱えていた何かから解放されたいと思っていたんだ。僕は本当に、真剣に、それを求めていたし、努力さえすればそれはいつか可能になるはずだと信じていた。でも結局のところ、僕はどこにもたどり着けなかったんだと思う。僕はどこまでいっても僕でしかなかった。僕が抱えていた欠落は、どこまでいってもあいかわらず同じ欠落でしかなかった。どれだけまわりの風景が変化しても、人々の語りかける声の響きがどれだけ変化しても、僕はひとりの不完全な人間に過ぎなかった。僕の中にはどこまでも同じ致命的な欠落があって、その欠落は僕に激しい飢えと渇きをもたらしたんだ。僕はずっとその飢えと渇きに苛まれてきたし、おそらくこれからも同じように苛まれていくだろうと思う。ある意味においては、その欠落そのものが僕自身だからだよ[3]。

ここに「欠落そのものが僕自身」という描写が見られる。これは、様々な場所を移動しながら、新しい場所や新しい生活とともに新しい人格を繰り返し作り続けていく中で、主体性が欠落したような感覚が芽生えてくるということだろう。この感覚が、世界中の人々の心を動かす村上春樹の作品の中で語られていることは、世界中の人々もまた、僕の生まれ育ちとどこか似通った暮らしを経験していることを示唆しているのではないだろうか。そして、「移動し続ける人生」において、根ざすものを失い、宙吊りにされる主体性が多くの人々にとっての現実なのであれば、主体性の問題を出発点にした作品制作についての言及から本稿を始めることに、まずはひとつの意義があると言えるのではないだろうか。

—

[1] UNWTO世界観光統計「International Tourism Results 2018 and Outlook 2019」によると、2010年に発表された長期予測では、海外旅行者総数は14億人到達が2020年になると見込まれていたが、2年前倒しで達成した。2030年には18億人に達する見込みであった。

[2] 本稿を執筆している2021年1月現在、コロナウイルスによるパンデミックで世界が動揺している。UNWTOは予測を下方修正し、海外旅行者数は、3〜6億人程度まで減少することが予測されている。

[3] 村上春樹(1995)『国境の南、太陽の西』講談社, pp.291-292

Ever since I was a child, I have lived in an apartment building on a national highway in the suburbs, because my father had to move around a lot. Perhaps because of this, I have always felt like an outsider or a rootless person wherever I went. Since I grew up, I have not consciously wanted to move, but I have not had any particular reason to stay in a particular place, so I have been moving from place to place all my life.

This way of life, in which “life itself is to keep moving” rather than to live rooted in a certain place, shakes the identity of human beings. But I think that this is actually a way of life that is inherent in many people living in today’s society. I would like to add that I am not an outdoorsy person, preferring to stay at home and read novels and philosophical books, but in spite of this, I have been moving from one country to another in Europe, South-East Asia and Africa for 17 years as a filmmaker and artist-in-residence. I’ve been to 17 countries in Europe, South East Asia and Africa. I don’t know whether this is a large number or a small one, but in this day and age, when urbanisation is making it easier for people to move around the world and the number of tourists is increasing at an unexpectedly rapid rate, as shown in the UNWTO’s World Tourism Statistics (Figure 1-1)[1], my “life on the move” symbolises one aspect of contemporary society. There is no doubt that my “life on the move” symbolises a part of modern society[2].

Figure 1-1 UNWTO World Tourism Statistics

I must have been about 18 years old when I got my first camera, a second-hand Fujica Z800 8mm film camera. It was a second-hand Fujica Z800 8mm film camera, capable of shooting three minutes on a single cassette, but without the correct colour temperature and exposure, it was impossible to shoot a normal landscape. More than 20 years have passed since then, and the camera has changed from some kind of Hi8 standard to the Sony VX2000, and after that I have been playing with digital cameras and iPhones, and recently I have been using the Panasonic GH series to record various images.

I’ve always been interested in film and experimental filmmaking, and of course I wanted to make my own images, but I think I was more interested in being involved in events with a camera. In this sense, today’s small, portable and highly functional cameras are much easier to use than in the past, in order to intervene in various events. In addition, the abundance of images in our daily life makes it less peculiar to intervene with a camera, and it is easier to establish a relationship with the subject while holding the camera.

In retrospect, my sense of rootlessness also made me lose the sense of being a part of the event, and I was imbued with a somewhat oblique quality that prevented me from being actively involved in the event, lacking initiative. But when I took a camera and got involved in an event, I felt the necessity of being there, even if I wasn’t a part of it, and that made me feel comfortable. The distance between me and the subject, the sense that I could be there and not feel uncomfortable, seemed to create a unique relationship between the people involved in the event and me. And it was a feeling that could only be felt through the camera.

Haruki Murakami (1949-) wrote a text in “South of the Border, West of the Sun” that symbolizes this sense of suspended perspective in the “in-between”, which is neither home nor abroad. This is a novel that was written more than 25 years ago.

I feel like in my life I’ve always been trying to somehow become a different person. I think I was always trying to go somewhere new, get a new life and develop a new personality there. I’ve done that many times before. In a way it was growth, in a way it was like a persona exchange. But anyway, I wanted to be free of something that I had been holding on to by becoming a different person. I really, seriously wanted that, and I believed that it would be possible one day if I just tried. But in the end, I didn’t get anywhere, I guess. I was just me, no matter how far I went. The lack I had was always the same lack, no matter how far I went. No matter how much the landscape around me changed, no matter how much the sound of people’s voices changed, I was still just one incomplete person. I had the same fatal lack inside me, and that lack brought me an intense hunger and thirst. I have always been tormented by that hunger and thirst, and I will probably continue to be tormented by it as well. In a way, that lack itself is me[3].

Here we find the description “the lack itself is me”. This could mean that as we move from place to place, repeatedly creating new personalities with new places and new lives, we develop a sense of missing subjectivity. The fact that this feeling is described in Haruki Murakami’s work, which touches the hearts of people all over the world, suggests that people all over the world are also experiencing a life somewhat similar to the one I was born and grew up with. And if the reality for many people is a subjectivity that loses its roots and is suspended in a “life of constant movement”, then it is significant to begin this article with a reference to the making of artworks that take the issue of subjectivity as their starting point.

—

[1] According to the UNWTO World Tourism Statistics “International Tourism Results 2018 and Outlook 2019”, according to the long-term forecast published in 2010, the total number of international travellers was expected to reach 1.4 billion in 2020, two years ahead of schedule. By 2030, the number was expected to reach 1.8 billion.

[2] As of this writing, in January 2021, the world is reeling from a coronavirus pandemic, and the UNWTO has revised its forecasts downwards, with the number of international travellers expected to fall to between 300 and 600 million.

[3] Haruki Murakami (1995), South of the Border, West of the Sun (Vintage International), Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. Kindle, p.208