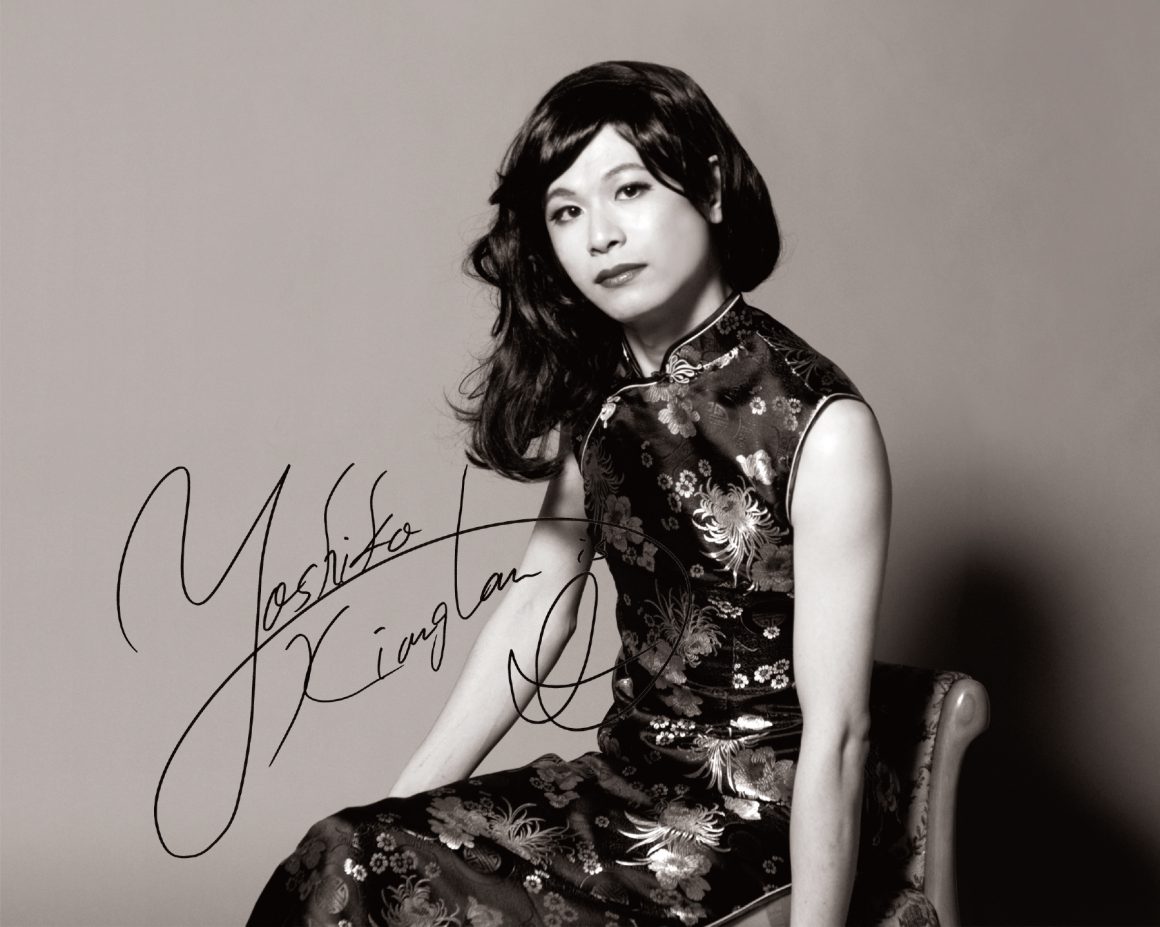

図3-1 澤崎賢一《よしことしゃんらんがわたし》

Fig. 3-1 Kenichi Sawazaki, Yoshiko, Xianglán is I

3. 他者への同化

3. Assimilation to others

展覧会「さかいにはさま、る しんこうけい」

積極的な「主体性の消失」の後に僕が試みたのは、「他者への同化」であった。その代表的な作品として、2012年にGALLERY TERRA TOKYO(東京)で開催された個展「さかいにはさま、る しんこうけい」(図3-1, 図3-2)で発表した映像作品《よしことしゃんらんがわたし[1]》と《ときのきせき[2]》の2つがある。

作品テーマは亡くなった僕の祖父・正恵(1918-2010)が残した戦争体験にまつわる日記により起因された。当事者としては体験し得ない正恵の戦争体験を、正恵と同化、或いは時代の空気とともに彼の体験をトレースすることで、僕自身が自分の祖父の戦争経験を追体験しようと試みた作品である。

この作品制作の動機は、2011年に発生した東日本大震災にあった。当時、僕は京都に在住していて、大阪の会社に勤務していた際に震災が発生した。このとき、当事者として震災に関わることのできない中、いったい何ができるのか、と考えていたときに僕は正恵の日記と再会した。被当事者として現実的にできることは、おそらく寄付だとかボランティアだとか、そういう活動になると考えられる。しかしこのときの僕の問いは、出来事から一定の距離感があるからこそ、芸術的実践として為すべきことがあるのではないか、ということであった。

Exhibition Progressive Belief in Doub, LE Bind

After the active “disappearance of subjectivity”, what I attempted was “assimilation to others”. Two representative works are Yoshiko, Xianglán is I [1] and Tracks of Past and Present [2], which were shown at the solo exhibition Progressive Belief in Doub, LE Bind (Fig. 3-1, Fig. 3-2) held at GALLERY TERRA TOKYO in 2012.

The theme of the work was inspired by the diary left by my late grandfather, Shoe (1918-2010), about his war experiences. The work is an attempt to relive my grandfather’s experience of war, which he could not have experienced as a witness, by either identifying with him or tracing his experiences with the atmosphere of the time.

The motivation for this work came from the Great East Japan Earthquake in 2011. At the time, I was living in Kyoto and working for a company in Osaka when the earthquake struck. At the time, I was wondering what I could do to help, as I was not involved in the disaster as an affected person, when I came across Shoe’s diary again. As a survivor, what I could realistically do would probably be to donate money, volunteer, and so on. However, my question at that time was whether there is something to be done as an artistic practice because of a certain distance from the event.

図3-2 澤崎賢一個展「さかいにはさま、る しんこうけい」の展示風景(筆者撮影)

Fig. 3-2 Kenichi Sawazaki solo exhibition Progressive Belief in Doub, LE Bind (Photo by the author)

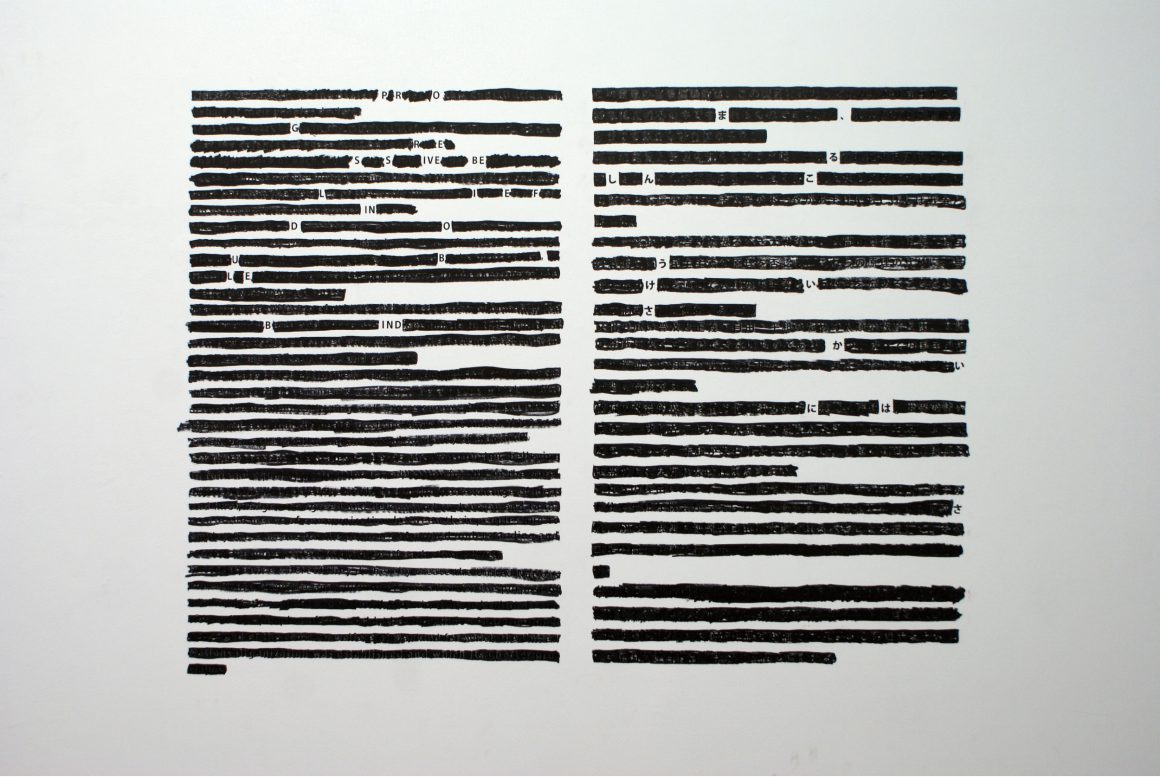

澤崎賢一(2012)《さかいにはさま、る しんこうけい》

インスタレーション(テキスト、カッティングシート、黒マジック)

Kenichi Sawazaki, Progressive Belief in Doub, LE Bind

Installation (text, cutting sheets, black felt pen)

映像作品《よしことしゃんらんがわたし》の中で、作者が朗読しているユネスコ憲章前文を壁面に掲示し、テキストをマジックで黒く塗りつぶすことにより、展覧会のタイトルが現れている。この作品は、第二次世界大戦後、日本において、国家主義や戦意を鼓舞する内容を抹消するために黒く塗られた教科書から着想を得ている。

The preamble to the UNESCO Charter, which is read by the artist in the video work Yoshiko, Xianglán is I, is displayed on the wall and the title of the exhibition appears by blackening the text with magic marker. The work is inspired by the textbooks that were blacked out in Japan after the Second World War in order to erase the nationalistic and war-motivated content.

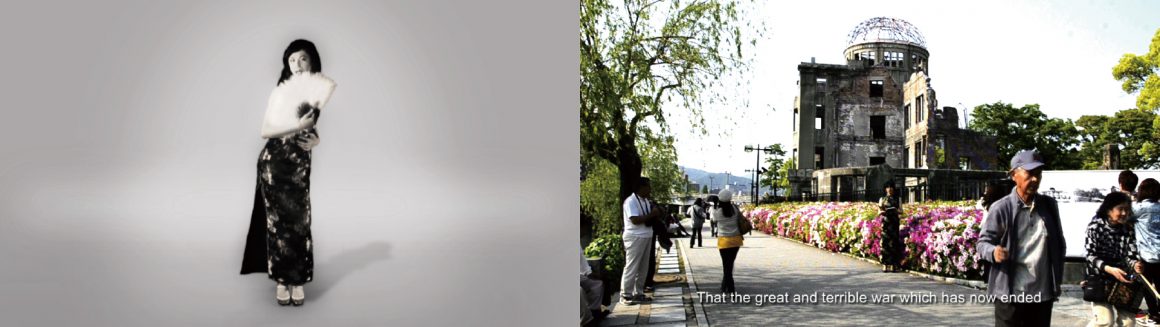

図3-3 澤崎賢一《よしことしゃんらんがわたし》の展示風景(筆者撮影)

Fig. 3-3 Kenichi Sawazaki, Yoshiko, Xianglán is I (Photo by the author)

実は、正恵の日記に「再会」という言い方をしたのには理由がある。正恵は、僕が幼少期の頃から実家の広島に帰省するたびに、戦争体験や彼の半生について綴った彼自身の編集による冊子を家族全員に配り続けていた。しかし僕は、震災のときまでそのことを半ば忘れかけていた。何か、これまで経験したことのないかたちで時代が変化しようとしていた。いまこそ、正恵が我々に伝えようとしたことと向き合うときなのではないか。これがこのときの作品制作の直接的な動機で、小さな個人史を出発点としたものではあったが、僕にとっては芸術的実践の存在意義が賭けられていた。

映像作品《よしことしゃんらんがわたし》は、正恵と同時代を生きた女優・李香蘭(1920-2014)に特殊メイクによって扮した僕が彼女の代表曲の1つ《蘇州夜曲[3]》を歌うプロモーション・ビデオ(PV)に見立てた映像(図3-4)と、李香蘭と僕自身のはざまの姿(メイクはせず、チャイナドレスを着ているのみ)で祖父が生前に暮らしていた広島へと京都から旅する記録映像(図3-5)、この2つで構成されるマルチスクリーンの映像作品である(図3-2)。広島への旅の道中には、正恵が亡くなった戦友へ贈った「ユネスコ憲章前文」の朗読を各所で行った。

Actually, there is a reason why I used the word “reunion” in Shoe’s diary. Whenever I returned to my parents’ home in Hiroshima from my childhood, Shoe would hand out to all the family a booklet that he had edited himself, describing his war experiences and his life. But I had almost forgotten about it until the earthquake. Something was about to change in a way that I had never experienced before. Now is the time to confront what Shoe was trying to tell us. This was the direct motivation for my work at that time, a small personal history as a starting point, but for me the raison d’être of my artistic practice was at stake.

The video work Yoshiko, Xianglán is I consists of two parts: a promotional video (fig. 3-4) in which I, dressed in special make-up as Li Xianglan (1920-2014), an actress who lived at the same time as Shoe, sing one of her most famous songs, Suzhou Nocturne[3]. In this multi-screen video work (Fig.3-5), I traveled from Kyoto to Hiroshima, where my grandfather had lived before his death, in a state between Li Xianglan and myself (without make-up, only wearing a Chinese dress) (Fig.3-2). On the way to Hiroshima, the preamble to the UNESCO Charter, which Shoe had given to her deceased comrades-in-arms, was read at various points.

図3-4 澤崎賢一《よしことしゃんらんがわたし》より

Fig. 3-4 Kenichi Sawazaki, Yoshiko, Xianglán is I

図3-5 作家自らが李香蘭に扮して《蘇州夜曲》を歌った映像

Fig. 3-5 A video work of the artist himself singing “Suzhou Nocturne” as Li Xianglan

図3-6 李香蘭と僕自身のはざまの姿で祖父が生前に暮らしていた広島へと京都から旅する記録映像

Fig. 3-6 A video of the artist’s journey from Kyoto to Hiroshima, the city where his grandfather lived before his death,

as a cross between Li Xianglan and the artist himself.

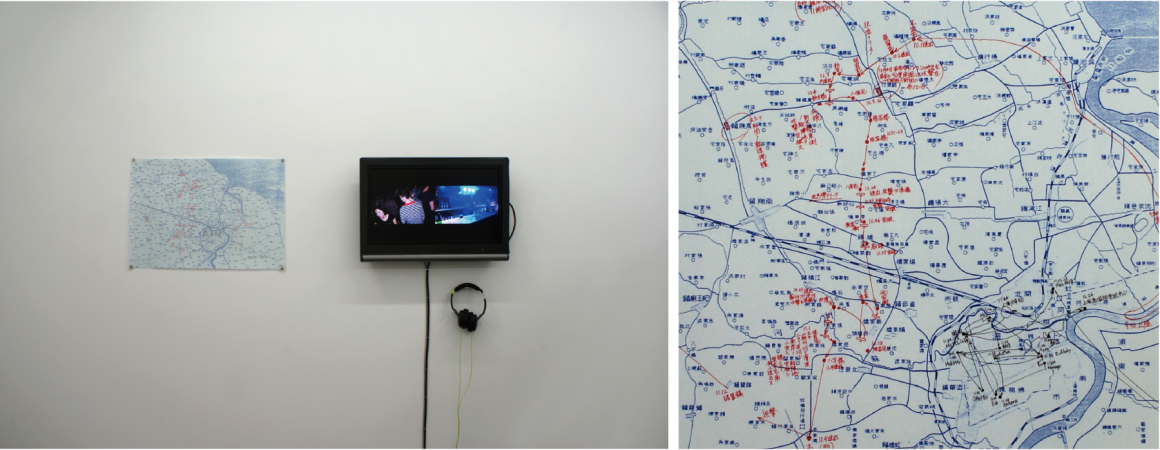

正恵は1937年に上海で勃発した第二次上海事件での従軍体験を日記に事細かに綴っているが、映像インスタレーション作品《ときのきせき》(図3-6)は、彼の当時の軌跡をたどることを目的に僕が上海に渡航して現在の上海を記録した映像作品である。

しかし、正恵がたどった軌跡をトレースするだけでは、僕自身がこの場所に赴いている意味や眼の前に起こっている出来事にきちんと向き合うことができないような気がして、途中で方向転換し、現地で知り合った人々との交流を記録する映像となった。展覧会では、2011年に僕が旅した道程と1937年に祖父が従軍した道程を記した地図も掲示した。

Shoe wrote in detail in his diary about his experiences of serving in the Second Shanghai Incident in 1937, and the video installation Tracks of Past and Present (Fig. 3-6) is a video work in which I traveled to Shanghai to record the present Shanghai with the aim of tracing the trajectory he followed at that time.

However, I felt that simply tracing the trajectory that Shoe had followed would not allow me to properly confront the meaning of my own visit to this place and the events that were happening in front of my eyes, and so I changed direction midway through the piece to record my interactions with the people I met there. In the exhibition I also displayed a map showing the route I took in 2011 and the route my grandfather took in 1937.

図3-7 澤崎賢一《ときのきせき》の展示風景(筆者撮影)

Fig. 3-7 Kenichi Sawazaki, Tracks of Past and Present (Photo by the author)

本作で僕が試みたことは、いったい何だったのだろうか。まず背景としては、《日常としての表象》の段で追求してきた「自律性」や「主体性」の袋小路から脱却するために、僕自身が社会と関わる必要性を感じていたということがある。密室から飛び出し、コンビニで買い物をするだけで緊張し、喜びを感じるような経験はそれまでになかった。たとえ機械的なイラッシャイマセという言葉と共に無感情に差し出されるお釣りを受け取るだけのやり取りにも、そこにいたるコンテクストによって人が何かしらの感情を揺さぶられるものなのだということに気がついたのである。

それゆえ僕は、身近なところから作品制作のための題材を導き出したかった。しかし僕にとって、自らの日常があまりにも平凡すぎるように感じられた。個展「さかいにはさま、る しんこうけい」が開催されたときには、僕は既に京都に移り住んでいた。それ以前は東京拘置所を駅のプラットフォームから臨む東武鉄道伊勢崎線小菅駅のそばに住んでおり、イベントの運営会社で朝から夜遅くまで毎日勤務していた。そのような中、僕がようやく興味を惹かれ見つけ出した作品の題材は次のような内容である。

東京駅の近くに勝手に里芋を植えて毎日帰宅途中で水をやり続けてそれを写真に撮る。たまたま右足の親指の爪が剥げるアクシデントがあり、その爪が元に戻るまで毎日親指を写真に撮り続ける。恋人が描いた絵をペンで執拗になぞる。そのような作品制作のための行為を日常生活のルーティンに組み込みながら、どこか悶々としていた。その折での東日本大震災である。

僕にとっての東日本大震災は、いまだに遠い出来事である。先にも述べたが、震災発生当時、僕は大阪にある別のイベント運営会社に勤務していた。大阪にあった勤務先のビルがかなり揺れたのを記憶しているが、被災地の状況をニュースなどで目の当たりにしながら、どのように受け止めてよいのか分からなかった。しかし、日々の暮らしに追われて時間はいつの間にか過ぎていった。しばらくしてから考えていたのは、出来事の被当事者として未曾有の災害から何を学ぶべきなのか、何と向き合えばよいのかということであった。そこで僕は自分の祖父・正恵と再会したのである。

正恵は生前、彼の戦争体験を事あるごとに家族に話し続けていた。だが、僕も含め、家族の誰も彼の話を自分のことのように受け止めることができなかった。そして正恵は亡くなり、広島にある僕の父の実家には正恵が著した日記や書籍の切り抜きなど、多くの冊子が残された。正恵はそこに次のような話を書いている。

1937年の第二次上海事変に一兵卒として従軍した際、彼の所属した部隊が壊滅したこと、彼は右足の太ももに大きな負傷を負い、既に死人だと認識されて命からがら日本に帰国したこと、自分だけが生き残ってしまったことを後ろめたく感じて、亡くなった戦友のことを常に思い続けていたことである。僕が映像作品《よしことしゃんらがわたし》の中で、広島各地で朗読しているユネスコ憲章前文は、正恵がこのとき亡くなった戦友に捧げたものである。それは「戦争は人の心の中で生まれるものであるから、人の心の中に平和のとりでを築かなければならない[4]」という言葉である。

ここで触れておきたいことは、大きな歴史には残ることのない、忘れ去られていくような個人的な歴史からでも、その歴史と向き合い多くを学ぶ可能性が、芸術的実践よって生み出され得るということである。また、そのための方法という点では、映像メディアの存在はとても大きいだろう。これは《日常としての表象》のときと同様だが、カメラのまなざしが向けられているからこそ、カメラの前に立つ者はその向こう側の世界を意識できるし、たったひとりの些細な関心に動機があったとしても、不特定多数の人々に向かって語りかけようとすることができるのである。

What is it that I have tried to do in this work? First of all, in order to break out of the impasse of “autonomy” and “subjectivity” that I had pursued in the a symbol as a daily life, I felt the need to get involved in society. Never before had I felt so nervous and happy just to step out of a closed room and go shopping at a convenience store. I realised that even a simple exchange of change, presented emotionlessly with a mechanical “iraschaimase(welcome)”, can move us in some way, depending on the context in which it takes place.

I therefore wanted to draw my subject matter for my work from my immediate surroundings. But for me, my own everyday life seemed too ordinary. I had already moved to Kyoto when my solo exhibition Progressive Belief in Doub, LE Bind was held. Before that I was living near Kosuge station on the Tobu Railway Isesaki line, with a view of the Tokyo Detention Centre from the station platform, and working every day from morning till late at night for an event management company. In the midst of all this, I finally found a subject for my art works that intrigued me, and it went something like this.

For example, I planted a taro near Tokyo Station without permission, watered it every day on my way home, and kept taking pictures of it. Or the accidental peeling of my right thumbnail, which I photographed every day until it was back to normal. I traced my girlfriend’s drawings with a ball-point pen. I was in a state of anguish as I incorporated this kind of work into my daily routine. Then came the Great East Japan Earthquake.

The Great East Japan Earthquake is still a distant memory for me. As I mentioned earlier, I was working for another event management company in Osaka when the earthquake struck. I remember that the building where I worked in Osaka shook quite a lot, but as I watched the news and saw the situation in the affected areas, I didn’t know what to make of it. However, I was so busy with my daily life that time passed before I knew it. After a while, I was thinking about what I should learn from this unprecedented disaster as a survivor and what I should do to face it. It was there that I met my grandfather, Shoe, again.

Before his death, Shoe kept on telling his family about his war experiences at every opportunity. But no one in the family, including myself, could accept his stories as if they were our own. When he died, my father’s house in Hiroshima was left with a number of booklets, including diaries and clippings from books that he had written. In them he wrote the following story.

When he served in the Second Shanghai Incident in 1937, his unit was destroyed; he was wounded so badly in his right thigh that he returned to Japan with his life in his hands, already recognized as a dead man; he felt guilty that he was the only one who survived, and kept thinking about his fallen comrades.

The preamble to the UNESCO Charter, which I recite at various locations in Hiroshima in my film Yoshiko, Xianglán is I, was dedicated by Shoe to his comrades-in-arms who died at that time. In its entirety, it says: “Since war is born in the hearts of men, we must build a bridge of peace in the hearts of men[4].

What I would like to mention here is that artistic practice can create the possibility to learn a lot by confronting personal histories that will not remain in the big histories, but will be forgotten. In terms of the methods used to achieve this, the presence of visual media is very significant. As in the case of a symbol as a daily life, the camera’s gaze allows the person standing in front of it to be aware of the world beyond, and to speak to an unspecified number of people, even if the motivation is only one person’s trivial interest.

映像を介した人間の生々しさ

The rawness of humanity through images

さらに述べておきたいことがある。それはこのとき《よしことしゃんらんがわたし》と共に制作した映像作品《ときのきせき》についてである。正恵が残した日記の中には、上海から蘇州へ彼がたどった戦時中の軌跡の記された地図が残されていた。初期の動機として、僕はそれら正恵の軌跡をたどることを目的に上海へと海を渡った。しかし結果的に撮影された映像には、現地で知り合ったアーティストや写真家、彼らの行きつけの居酒屋やナイトクラブ巡りの様子が記録された。そこに記録された映像には、当然ながら正恵が従軍したときの上海は存在しない。つまり僕は、渡航前には正恵の軌跡を丁寧にたどることを目的としていたのだが、途中から彼の軌跡を追うのを中止して、現在の僕自身の体験を記録したのである。

これはなぜだろうか。振り返ると、実際に上海に降り立ったとき、街の喧騒や人々との出会い、思いがけぬ出来事などがたくさんあったのだが、それらを無視してやり過ごすことが、僕にはできなかったのである。さらに、使用したカメラはプロ仕様の大掛かりなものではなく、偶然に予備用に持参していた小さなコンパクトデジタルカメラ(コンデジ)であり、僕は気に掛かる出来事が生じるごとにさっとポケットからそのコンデジを取り出して撮影していた。これはとても肉体的あるいは直感的な反応で、理論的な動機に基づくものではない。撮影する段階では、歴史を振り返ろうとしたり、アーカイブしようとしたりすることよりも、個人的な経験からどのように反応するか、ということが根本的な動機として存在していた。どのような動機であれ、どこかの場所を訪れ、何かにまなざしを向けようとするとき、目の前で起こっている出来事のアクチュアリティに触れるために敏感であることは、とても重要である。

さて、ここまで展覧会「さかいにはさま、る しんこうけい」についてその制作過程を述べてきたが、本作には、社会と関わる表現において肝要な心構えとともに、いぜん明確に意識されてはいないものの、映像メディアを介することによって出来事に関わる際の特徴を見ることができる。その特徴とは、写真や映像といったイメージの中に、匿名性を超えた人間の生々しさが映り込むことである。ベンヤミンが、その著作「写真小史」の中で、写真の最初期のうちにイギリスの写真家デイヴィッド・オクタヴィアス・ヒル(1802 –1870)が撮影した無名のひとびとの映像について書いた言葉に、匿名性を超えた人間の生々しさが表れている。

同じ題材はとうから絵画にもあった。無名の人物像も、家族の手の中にあるかぎり、そこにえがかれている人物のことは、ときどき話題になった。けれども、二、三世代もたつと、そういう関心は消えてしまう。絵画がなおかつ残るとすれば、それは、それをえがいた者の技倆のあかしとしてにすぎない。しかし写真の場合には、何か新しい特異なことが起こる。こわばりのない、誘惑的な恥じらいを見せて顔をうつむけている、あのニナヘヴンの漁村の女の写真には、写真家ヒルの技倆のあかしというだけでは割り切れない何かが、まだ残るのだ。黙視できないその何かは、かつて生活していた女、そしてこの写真の上でいまなお現実的であり、けっして完全には〈芸術〉にとりこまれようとしない女の名前を、執助にもとめてやまない。「そしてぼくは問う、この優美な髪やまなざしは/かつてどのようにひとや物と触れあったか、/いま欲望が焔のない煙のように無意味に絡んでゆく/このくちびるは、どのようにくちづけしたか。」〔…〕写真家の技倆も、モデルの身ごなしの計画性も疑えないが、こういう写真を見るひとは、その写真のなかに、現実がその映像の性格を焼き付けるのに利用した一粒の偶然を、凝縮した時空を探しもとめずにはいられない気がしてくる。その目立たない場、もはやとうに過ぎ去ったあの分秒のすがたのなかに、未来のものが、こんにちもなお雄弁に宿っていて、われわれは回顧することによってそれを発見することができるのだから。じじつ、カメラに語りかける自然は、眼に語りかける自然とは違う。その違いは、とりわけ、人間の意識に浸透される空間の代わりに、無意識に浸透された空聞が現出するところにある[5]。

野村修(1930-1998)は、このベンヤミンのテキストを引用しながら、「ここではアウラという語は用いられていないが、「割り切れない何か」、「凝縮した時空」、「無意識に浸透された空間」といった表現で語られている内実は、明らかに、初期の写真がおびたアウラだろう」と述べている[6]。ここで僕が考えたいのは、ベンヤミンが最初期の写真に感じたものと近い感覚が、現代の身体的かつ直感的なモバイルなデバイスカメラが記録した映像にも、少なからず表れうるのではないか、ということである。

《ときのきせき》の制作を通じて、僕が面白いと感じたのは、当初主題として考えていた祖父の戦争体験と向き合うプロセスにおいて、僕自身の旅の経験が結果的にこの作品の中心となっていき、主題が図らずもズレていったことである。主題はどうしてズレていったのだろうか。また、このとき映像メディアは、どんな機能を果たしたのだろうか。

その理由として僕は、映像メディアを介して出来事に関わる際、写真や映像といったイメージの中に匿名性を超えた人間の生々しさが映り込んでおり、そこに写り込んでいるものが僕自身に多くを語りかけてきたから、こうした感覚が生まれてきたのではないか、と思うのである。僕が感じた映像に映り込んだ生々しさには、野村の述べたような「アウラ」と共通するものも存在しているのではないかとも考える。しかし、何よりも芸術実践のプロセスにおいて、イメージの生々しさが実践の内容の方向性にまで強く影響を及ぼしうるのだということに敏感であるべきなのではないだろうか。

—

[1] 澤崎賢一(2012)《よしことしゃんらんがわたし》映像インスタレーション, 3分50秒

[2] 澤崎賢一(2012)《ときのきせき》映像インスタレーション, 16分13秒, 地図 420×297cm

[3] 《蘇州夜曲》は、1940年に制作された映画『支那の夜』(伏水修監督)の中で李香蘭が歌った曲である。祖父・正恵は、第二次上海事変(1937年)の際、陸軍の兵士として蘇州に従軍した。翌1938年に山口淑子は、満州国の国策映画会社・満洲映画協会から中国人の専属映画女優「李香蘭」としてデビューした。

[4] 「ユネスコ憲章」の正式名称は「国際連合教育科学文化機関憲章」。国際連合教育科学文化機関(ユネスコ)の設立根拠となる条約。

[5] ヴァルター・ベンヤミン(1970)「写真小史」田窪清秀・野村修訳, p73,『ヴァルター・ベンヤミン著作集2』晶文社

[6] 野村修(1991)「ベンヤミンにおけるアウラの概念」ドイツ文學研究, 36: p.62

I would like to mention one more thing. I would like to mention something more about the video work Tracks of Past and Present, which was made at this time together with Yoshiko, Xianglán is I. In the diary that Shoe left behind, there was a map of his wartime journey from Shanghai to Suzhou. My initial motivation was to cross the sea to Shanghai with the intention of following the path of Shoe. In the end, however, the images I shot documented the artists and photographers I met there, and their visits to the pubs and nightclubs they frequented. Of course, the images recorded there do not include Shanghai, where Shoe served in the army. In other words, before I went to Shanghai, my aim was to carefully trace the trajectory of Shoe’s life, but halfway through the trip, I stopped following his path and recorded my own experiences in the present.

I wonder why this is? In retrospect, when I actually landed in Shanghai, I couldn’t just ignore the hustle and bustle of the city, the people I met and the many unexpected things that happened. Furthermore, the camera I used was not a big professional one, but a small compact digital camera that I happened to have with me as a backup, and which I quickly took out of my pocket to take pictures of every event that occurred to me. This was a very physical and intuitive reaction, not based on any theoretical motivation. The underlying motivation for taking the pictures was not so much to look back or archive history, but to see how I would react to my personal experiences. Whatever the motivation, when you visit a place and try to fix your gaze on something, it is very important to be sensitive in order to get in touch with the acutality of the events taking place in front of you.

So far I have described the process of making the exhibition Progressive Belief in Doub, LE Bind. In this work, we can see a characteristic, though not yet explicitly conscious, of the engagement with events through the medium of images, as well as an important attitude in the expression of social engagement. This characteristic is the reflection in the photographic or filmic image of a human rawness that goes beyond anonymity. Benjamin’s words in his book A Short History of Photography about the images of anonymous people taken by the English photographer David Octavius Hill (1802 – 1870) in the early days of photography reveal a human vividness that transcends anonymity.

The same subject has always existed in painting. Even unknown figures, as long as they remained in the hands of the family, were sometimes the subject of conversation. After two or three generations, however, this interest disappears. If a painting still remains, it is only as a testimony to the skill of the person who painted it. In the case of photography, however, something new and peculiar happens. In the photograph of the woman in the fishing village of Nina Haven, with her face turned down in a stiff, seductive shame, there is still something that cannot be reduced to a testimony to the skill of the photographer Hill. That something that cannot be silenced persists in seeking the name of the woman who once lived, the woman who is still real in this photograph, and who has never been completely absorbed into ‘art’. And I ask, how did this graceful hair and gaze once touch people and things, and how did this lip kiss, where desire now twines meaninglessly like smoke without flame? (…) I do not doubt the skill of the photographer or the planning of the model’s body, but the viewer of such a photograph cannot help looking for in it a condensed space-time, a grain of chance that reality has used to burn the character of the image. For in that inconspicuous place, in the shape of those minutes and seconds that have already passed, the future still dwells eloquently, and we can discover it in retrospect. In fact, the nature that speaks to the camera is different from the nature that speaks to the eye. The difference lies, among other things, in the fact that instead of a space permeated by human consciousness, an empty space permeated by the unconscious appears [5].

Osamu Nomura (1930-1998), quoting from Benjamin’s text, says: “Although the word aura is not used here, the substance of what is described by the expressions ‘something indivisible’, ‘condensed space-time’ and ‘unconsciously permeated space’ is clearly the aura of the early photographs[6]. What I would like to consider here is that the same sensations that Benjamin felt in his early photographs may also be expressed in no small measure in the images recorded by the mobile, physical and intuitive devices of the modern camera.

What I found interesting about the process of making Tracks of Past and Present was that in the process of confronting my grandfather’s war experience, which I had initially thought of as the subject, my own experiences of travel ended up becoming central to the work, and the subject shifted in an unintentional way. Why did the subject matter shift? And what function did the visual media play in this process?

The reason for this, I think, is that when I am involved in events through the visual media, the rawness of human beings beyond anonymity is reflected in images such as photographs and videos, and these images speak to me in many ways. I think that the vividness I felt in the images may have something in common with the “aura” described by Nomura. But above all, we should be sensitive to the fact that in the process of artistic practice, the vividness of the image can strongly influence the direction of the content of the practice.

[1] 澤崎賢一(2012)《よしことしゃんらんがわたし》映像インスタレーション, 3分50秒

[2] 澤崎賢一(2012)《ときのきせき》映像インスタレーション, 16分13秒, 地図 420×297cm

[3] 《蘇州夜曲》は、1940年に制作された映画『支那の夜』(伏水修監督)の中で李香蘭が歌った曲である。祖父・正恵は、第二次上海事変(1937年)の際、陸軍の兵士として蘇州に従軍した。翌1938年に山口淑子は、満州国の国策映画会社・満洲映画協会から中国人の専属映画女優「李香蘭」としてデビューした。

[4] 「ユネスコ憲章」の正式名称は「国際連合教育科学文化機関憲章」。国際連合教育科学文化機関(ユネスコ)の設立根拠となる条約。

[5] ヴァルター・ベンヤミン(1970)「写真小史」田窪清秀・野村修訳, p73,『ヴァルター・ベンヤミン著作集2』晶文社

[6] 野村修(1991)「ベンヤミンにおけるアウラの概念」ドイツ文學研究, 36: p.62